12. Monte Carlo Methods

29 Sep 2019 | Reinforcement Learning

Montel Carlo(MC) Methods Introduction

- Last Section: Dynamic Programming

- would that work for self-driving cars or video games?

- can i just set the state of the agent?

- “god-mode” capabilities?

- MC Methods learn purely from experience

- Montel Carlo usually refers to any method with a significant random component

- Random Component in RL is the return

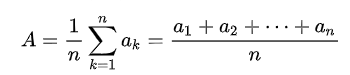

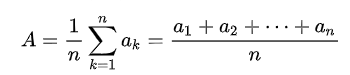

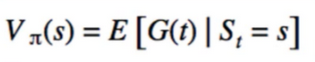

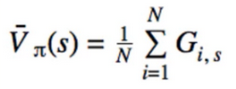

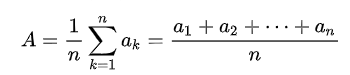

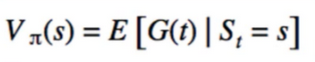

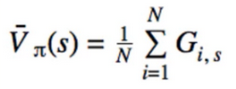

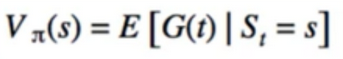

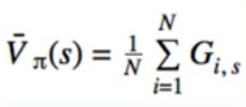

- With MC, instead of calculating the true expected value of G, we calculate its sample mean

- Need to assume episode tasks only

- Episode must terminate before we calculate return

- Not “fully” online since we need to wait for entire episode to finish before updating

- (full online mean is update after every action)

- monte carlo methods is not fully online which mean it is updated after episode to finish

- Should Remind you of multi-armed bandit

- Multi-Armed bandit : average reward after every action

- MDPs: average the return

- One way to think of MC-MDP is every state is a separate multi-armed bandit problem

- Follow the same pattern

- Prediction Problem(Finding Value given policy)

- Control Problem(finding optimal policy)

1. Monte Carlo for prediction Problem

How do we generate G?

- just play a bunch of episode, log the states and reward sequences

s1 s2 s3 ... sT

r1 r2 r3 ... rT

-

Calculate G from Definition:

G(t) = r(t+1)+gamma*G(t+1)

- very helpful to calculate G by iterating through states in reverse order

- Once we have(s,G) pairs, average them for each s

Multiple Visits to s

- what if we see the same state more than once in an episode

- E.g. we see s at t=1 and t=3

- which return should we use? G(1) or G(3

- First-visit method :

- Use t = 1 only

- Every-visit method :

- Use both t=1 and t=3 as samples

- Surprisingly, it has been proven that both lead to same answer

First-Visit MC Pseudocode

def first_visit_monte_carlo_prediction(π, N):

V = random initialization

all_return = {} # default = []

do N times:

states, returns = play_episode

for s, g in zip(states, returns):

if not seen s in this episode yet:

all_return[s].append(g)

V(s) = sample_mean(all_returns[s])

return V

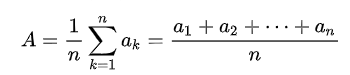

Sample Mean

- Notice how we store all returns in a list

- Didn’t we discuss how that’s inefficient?

- Can also use previous mean to calculate current mean

- Can also use moving average for non-stationary problems

- Everything we learned before still applies

- Rules of probability still apply

- Central limit Theorem

- Variance of estimate = Variance of RV(Random Value) / N

Calculating Returns from Rewards

s = grid.current_state()

states_and_rewards = [(s,0)]

while not game_over:

a = policy(s)

r = grid.move(a)

s = grid.current_state()

states_and_rewards.append((s,r))

G = 0

states_and_returns = []

for s,r in reverse(states_and_rewards):

states_and_returns.((s,G))

G = r + gamma*G

states_and_returns.reverse

MC

- Recall: one Disadvantage of DP is that we need to loop through all states

- MC: only update V for visited states

- We don’t even need to know what all the states are, we can just discover them as we play

2. MC for Windy Gridworld

- Windy Gridworld, different policy

- Policy/transitions were deterministic, MC not really needed

- in windy gridworld, p(s’r I s,a) not deterministic

- with this policy, we try to get to goal

- Values can be -ve, if overall wind pushes us to losing state more often

code

# https://deeplearningcourses.com/c/artificial-intelligence-reinforcement-learning-in-python

# https://www.udemy.com/artificial-intelligence-reinforcement-learning-in-python

from __future__ import print_function, division

from builtins import range

# Note: you may need to update your version of future

# sudo pip install -U future

import numpy as np

from grid_world import standard_grid, negative_grid

from iterative_policy_evaluation import print_values, print_policy

SMALL_ENOUGH = 1e-3

GAMMA = 0.9

ALL_POSSIBLE_ACTIONS = ('U', 'D', 'L', 'R')

# NOTE: this is only policy evaluation, not optimization

def random_action(a):

# choose given a with probability 0.5

# choose some other a' != a with probability 0.5/3

p = np.random.random()

if p < 0.5:

return a

else:

tmp = list(ALL_POSSIBLE_ACTIONS)

tmp.remove(a)

return np.random.choice(tmp)

def play_game(grid, policy):

# returns a list of states and corresponding returns

# reset game to start at a random position

# we need to do this, because given our current deterministic policy

# we would never end up at certain states, but we still want to measure their value

start_states = list(grid.actions.keys())

start_idx = np.random.choice(len(start_states))

grid.set_state(start_states[start_idx])

# random start

s = grid.current_state()

states_and_rewards = [(s, 0)] # list of tuples of (state, reward)

while not grid.game_over():

a = policy[s]

a = random_action(a)

r = grid.move(a)

s = grid.current_state()

states_and_rewards.append((s, r))

# calculate the returns by working backwards from the terminal state

G = 0

states_and_returns = []

first = True

for s, r in reversed(states_and_rewards):

# the value of the terminal state is 0 by definition

# we should ignore the first state we encounter

# and ignore the last G, which is meaningless since it doesn't correspond to any move

if first:

first = False

else:

states_and_returns.append((s, G))

G = r + GAMMA*G

states_and_returns.reverse() # we want it to be in order of state visited

return states_and_returns

if __name__ == '__main__':

# use the standard grid again (0 for every step) so that we can compare

# to iterative policy evaluation

grid = standard_grid()

# print rewards

print("rewards:")

print_values(grid.rewards, grid)

# state -> action

# found by policy_iteration_random on standard_grid

# MC method won't get exactly this, but should be close

# values:

# ---------------------------

# 0.43| 0.56| 0.72| 0.00|

# ---------------------------

# 0.33| 0.00| 0.21| 0.00|

# ---------------------------

# 0.25| 0.18| 0.11| -0.17|

# policy:

# ---------------------------

# R | R | R | |

# ---------------------------

# U | | U | |

# ---------------------------

# U | L | U | L |

policy = {

(2, 0): 'U',

(1, 0): 'U',

(0, 0): 'R',

(0, 1): 'R',

(0, 2): 'R',

(1, 2): 'U',

(2, 1): 'L',

(2, 2): 'U',

(2, 3): 'L',

}

# initialize V(s) and returns

V = {}

returns = {} # dictionary of state -> list of returns we've received

states = grid.all_states()

for s in states:

if s in grid.actions:

returns[s] = []

# 빈값을 넣어는다 initializize

else:

# terminal state or state we can't otherwise get to

V[s] = 0

# repeat until convergence

# 5000 iterative

for t in range(5000):

# generate an episode using pi

states_and_returns = play_game(grid, policy)

seen_states = set()

for s, G in states_and_returns:

# check if we have already seen s

# called "first-visit" MC policy evaluation

if s not in seen_states:

returns[s].append(G)

V[s] = np.mean(returns[s])

seen_states.add(s)

print("values:")

print_values(V, grid)

print("policy:")

print_policy(policy, grid)

2. MC for Control Problem

- Let’s now move on to control problem

- Can we use MC?

- Problem: we only have V(s) for a given policy, we don’t know what actions will lead to better V(s) because we can’t do look-ahead search

- only play episode and get states/returns

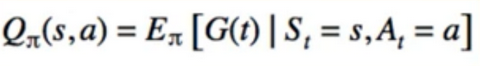

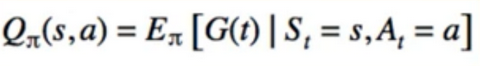

- key is to use Q(s,a)

- we can choose argmax[a]{Q,a}

MC for Q(s,a)

- simple modification

- instead of list of tuples(s,G)

- return list of triples(s,a,G)

Problem with Q(s,a)

- with V(s) we only need ISI different estimates

- with Q(s,a) we need IsI x IAI different estimates

- Many more iterations of MC are needed

- should remind us of explore-exploit dilemma

- if we follow a fixed policy, we only do 1 action per state

- we can only fill in ISI / (ISI x IAI) = 1 / IAI values in Q

- Can fix it by using the “exploring-starts” methods

- we choose a random initial state and a random initial action

- thereafter follow policy

- this is consistent with our definition of Q :

Back to Control Problem

- if we think actually, we’ll realize we already know the answer

- Generalized policy iteration:

- Alternate between policy evaluation and policy improvement

- we know how to do evaluation

- policy improvement same as always : π(s) = $argmax_s$Q(s,a)

Problem with MC

- Problem: same as before - we have an iterative algorithm inside an iterative algorithm

- For Q we need lots of samples

3. Solution

- Similar value iteration

- Do not start a fresh MC evaluation on each round

- would take too long to collect samples

- instead, just keep updating the same Q

- Do policy improvement after every episode

- therefore, generate only one episode per iteration

Pseudocode

```

Q = random, pi =random

While True :

s, a = randomly select from S and A

states_actions_returns = play_game(start=(s,a))

for s,a,G in state_actions_returns:

returns(s,a).append(G)

Q(s,a) = average(returns(s,a))

for s in states:

pi(s) = argmax[a]{Q(s,a)}

```

Another Problem with MC

- What if policy includes an action that bumps into a wall?

- we end up in same state as before

- if we follow this policy, episode will never finish

- Hack:

- if we end up in same state after doing action, give this a reward of -100, and end the episode

MC-ES

- Interesting fact: this converges even though the samples for Q are for different policies

- if Q is suboptimal, then policy will change, causing Q to change

- we can only achieve stability when both value and policy converge to optimal value and optimal policy

- Another interesting fact: this has never been formally proven

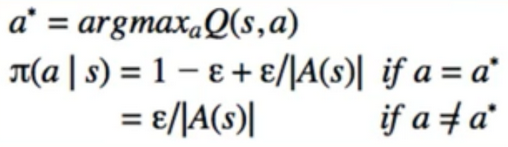

4. MC Control without ES

- Disadvantage of previous control method : needs exploring starts

- Could be infeasible(不可能的) for games we are not playing in “god-mode”

- E.g Self-driving car

- remove need for ES(exploring starts)

- Recall: all the techniques we learned for the multi-armed bandit are applicable here

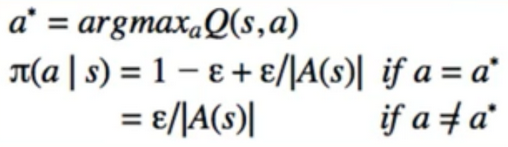

- let’s not be greedy, but epsilon-greedy instead

- code modification:

- Remove exploring starts

- change policy to sometimes be random

- Epsilon-soft

- But we also use epsilon to decide if we want to explore:

- From now on, we’ll just refer to this as epsilon-greedy

추가 설명

- 즉 해보지 않은 행동에 대해서도 가끔 선택할 수 있게 하는 방법

- 방법에는 두가지가 있다

- On-policy : 결정했던 행동들을 가지고 정책을 평가 발전한다

- Off-Policy : 다른 방법에 의해 만들어진 데이터로 정책 평가와 발전한다.

- Monte Carlo ES는 On-Policy

- Monte Carlo without ES 는 Off-Policy

- On-policy Control 방법은 정책이 Soft 하다. Soft의 뜻은 정책의 모든 확률이 0 이상, 즉 초기에 모든 행동을 일정 확률로 할 가능성이 있다가 점점 결정적인 최적의 정책으로 바뀐다(deterministic Optimal Policy).

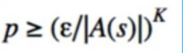

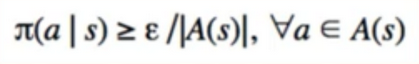

- Off-Policy Control은 Epsilon Greedy 방법을 이용하여 랜덤하게 행동을 선택할 확률 최소값은 Epsilon / IA(s)I 이며, 나머지 확률 1-epsilon+epsilon/IA(s)I 로 greedy 행동을 취한다. (1-epsilon에 epsilon/IA(s)I 추가한 이유는 랜덤하게 하는 행동중 하나가 이 greedy로 행동 할 것이기 때문이다.)

- epsilon-greedy 정책은 확률이 π(a I s) >= epsilon/IA(s)I로, e-soft policy의 예이다.

- 즉 exporing starts 가정 없이 탐험을 할 수 없기 때문에 무작정 가치를 따라 Greedy하게 행동하도록 할 수 없다.

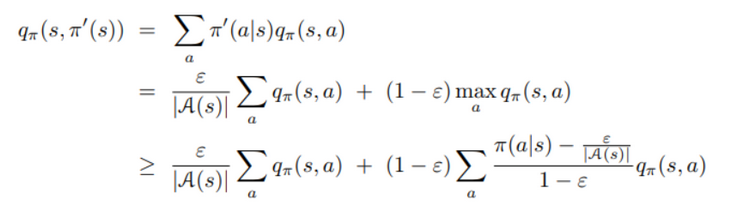

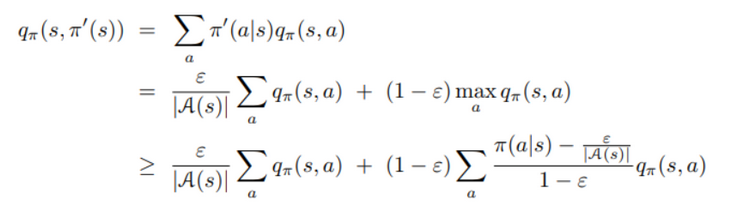

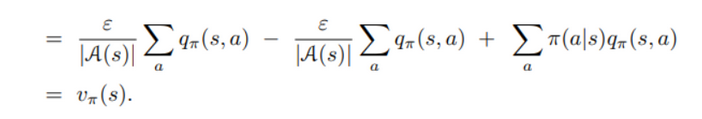

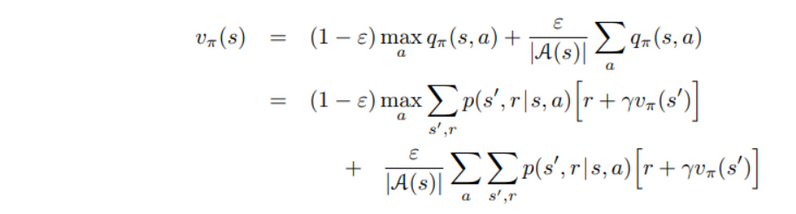

- epsilon-greedy policy 또한 정책 개선 이론에 따라 확실히 개선된다. π’를 epsilon-greedy policy라고 하였을 때( weighted average가 1 이고, 가장 큰 수보다 작거나 같다. 아래식은 모든 행동에 대한 확률의 합이 1이 되도록 한 식이다.)

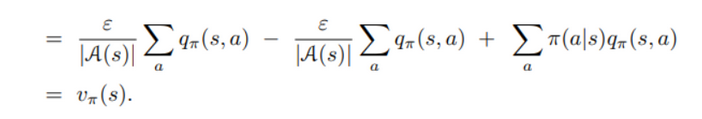

- 결국 정책 x의 가치의 합이기 때문에 이는 상태 가치홤수와 같다. 결국 $q_π$(s,π’(s))>=$v_π$(s) 이므로, 정책 개선 이론에 따라 π’>=π(즉 $v+π$(s)>=$v_π$(s))가 된다.

-

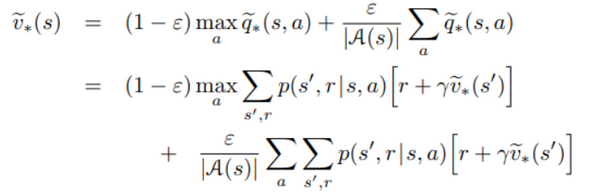

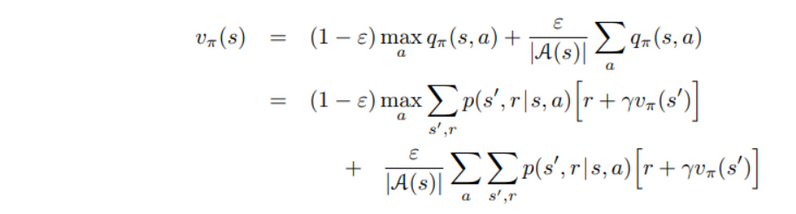

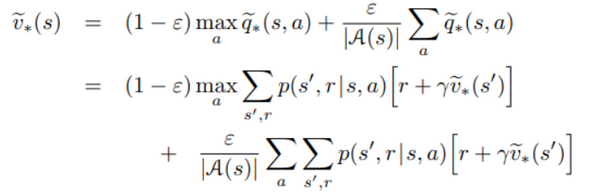

epsilon-soft policy 과에 차이점은 epsilon-soft가 들어갔다는 차이밖에 없다. 동일한 행동과 상태들, epsilon에 따라 랜덤한 행동을 하는 것까지 같다. 아래에 variable $v_$^~ $q_$^~ 이 새로운 환경에 최적의 가치 함수들이라고 하자. 그럼 epsilon-soft policy 는 $v_π$ = $v_π$^~라면 π는 최적이라고 할 수 있을 것이다.

- $v_π$ = $v_π$^~ 로 바꾸면

- Policy iteration은 epsilon-soft policy 에도 적용이 된다는 것을 보였을 것이다. epsilon-soft-poilicy 에 greedy policy를 적용하면 매 step마다 개선이 확실 된다는 것을 보이며, exploring starts를 제거했다.

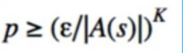

How often will we reach off-policy states?

- Consider a state K steps away from the start

- the probability that we get there by pure exploration is small

- we need to run MC many times to converge for these states

5. MC Summary

- Last Section, DP: we knew all the state transition probability and never played the game

- this section: learn from experience

- main idea: approximate the expected return with sample mean

- First-visit and every-visit

MC VS DP

- MC can be more efficient than DP because we don’t need to loop through all states

- But also means we might not get the “full” value function, since some states will never be reached or reached very rarely

- more data -> more accuracy

- We used exploring starts to ensure we had adequate data for each state

MC Control

- Use Q instead of V

- No look-ahead search

- Problem: MC loop inside another loop

- We took the same approach as value iteration: update the policy after every episode, keep updating the same Q in-place

- Surprising: it converges even though the samples are not all for the same policy

- Never formally proved to converge

- we then removed exploring starts assumption by replacing it with epsilon-greedy

- MDPs are like different multi-armed bandit problem at each state

Reference:

Artificial Intelligence Reinforcement Learning

Montel Carlo(MC) Methods Introduction

- Last Section: Dynamic Programming

- would that work for self-driving cars or video games?

- can i just set the state of the agent?

- “god-mode” capabilities?

- MC Methods learn purely from experience

- Montel Carlo usually refers to any method with a significant random component

- Random Component in RL is the return

- With MC, instead of calculating the true expected value of G, we calculate its sample mean

- Need to assume episode tasks only

- Episode must terminate before we calculate return

- Not “fully” online since we need to wait for entire episode to finish before updating

- (full online mean is update after every action)

- monte carlo methods is not fully online which mean it is updated after episode to finish

- Should Remind you of multi-armed bandit

- Multi-Armed bandit : average reward after every action

- MDPs: average the return

- One way to think of MC-MDP is every state is a separate multi-armed bandit problem

- Follow the same pattern

- Prediction Problem(Finding Value given policy)

- Control Problem(finding optimal policy)

1. Monte Carlo for prediction Problem

How do we generate G?

- just play a bunch of episode, log the states and reward sequences

s1 s2 s3 ... sT r1 r2 r3 ... rT -

Calculate G from Definition: G(t) = r(t+1)+gamma*G(t+1)

- very helpful to calculate G by iterating through states in reverse order

- Once we have(s,G) pairs, average them for each s

Multiple Visits to s

- what if we see the same state more than once in an episode

- E.g. we see s at t=1 and t=3

- which return should we use? G(1) or G(3

- First-visit method :

- Use t = 1 only

- Every-visit method :

- Use both t=1 and t=3 as samples

- Surprisingly, it has been proven that both lead to same answer

First-Visit MC Pseudocode

def first_visit_monte_carlo_prediction(π, N):

V = random initialization

all_return = {} # default = []

do N times:

states, returns = play_episode

for s, g in zip(states, returns):

if not seen s in this episode yet:

all_return[s].append(g)

V(s) = sample_mean(all_returns[s])

return V

Sample Mean

- Notice how we store all returns in a list

- Didn’t we discuss how that’s inefficient?

- Can also use previous mean to calculate current mean

- Can also use moving average for non-stationary problems

- Everything we learned before still applies

- Rules of probability still apply

- Central limit Theorem

- Variance of estimate = Variance of RV(Random Value) / N

Calculating Returns from Rewards

s = grid.current_state()

states_and_rewards = [(s,0)]

while not game_over:

a = policy(s)

r = grid.move(a)

s = grid.current_state()

states_and_rewards.append((s,r))

G = 0

states_and_returns = []

for s,r in reverse(states_and_rewards):

states_and_returns.((s,G))

G = r + gamma*G

states_and_returns.reverse

MC

- Recall: one Disadvantage of DP is that we need to loop through all states

- MC: only update V for visited states

- We don’t even need to know what all the states are, we can just discover them as we play

2. MC for Windy Gridworld

- Windy Gridworld, different policy

- Policy/transitions were deterministic, MC not really needed

- in windy gridworld, p(s’r I s,a) not deterministic

- with this policy, we try to get to goal

- Values can be -ve, if overall wind pushes us to losing state more often

code

# https://deeplearningcourses.com/c/artificial-intelligence-reinforcement-learning-in-python

# https://www.udemy.com/artificial-intelligence-reinforcement-learning-in-python

from __future__ import print_function, division

from builtins import range

# Note: you may need to update your version of future

# sudo pip install -U future

import numpy as np

from grid_world import standard_grid, negative_grid

from iterative_policy_evaluation import print_values, print_policy

SMALL_ENOUGH = 1e-3

GAMMA = 0.9

ALL_POSSIBLE_ACTIONS = ('U', 'D', 'L', 'R')

# NOTE: this is only policy evaluation, not optimization

def random_action(a):

# choose given a with probability 0.5

# choose some other a' != a with probability 0.5/3

p = np.random.random()

if p < 0.5:

return a

else:

tmp = list(ALL_POSSIBLE_ACTIONS)

tmp.remove(a)

return np.random.choice(tmp)

def play_game(grid, policy):

# returns a list of states and corresponding returns

# reset game to start at a random position

# we need to do this, because given our current deterministic policy

# we would never end up at certain states, but we still want to measure their value

start_states = list(grid.actions.keys())

start_idx = np.random.choice(len(start_states))

grid.set_state(start_states[start_idx])

# random start

s = grid.current_state()

states_and_rewards = [(s, 0)] # list of tuples of (state, reward)

while not grid.game_over():

a = policy[s]

a = random_action(a)

r = grid.move(a)

s = grid.current_state()

states_and_rewards.append((s, r))

# calculate the returns by working backwards from the terminal state

G = 0

states_and_returns = []

first = True

for s, r in reversed(states_and_rewards):

# the value of the terminal state is 0 by definition

# we should ignore the first state we encounter

# and ignore the last G, which is meaningless since it doesn't correspond to any move

if first:

first = False

else:

states_and_returns.append((s, G))

G = r + GAMMA*G

states_and_returns.reverse() # we want it to be in order of state visited

return states_and_returns

if __name__ == '__main__':

# use the standard grid again (0 for every step) so that we can compare

# to iterative policy evaluation

grid = standard_grid()

# print rewards

print("rewards:")

print_values(grid.rewards, grid)

# state -> action

# found by policy_iteration_random on standard_grid

# MC method won't get exactly this, but should be close

# values:

# ---------------------------

# 0.43| 0.56| 0.72| 0.00|

# ---------------------------

# 0.33| 0.00| 0.21| 0.00|

# ---------------------------

# 0.25| 0.18| 0.11| -0.17|

# policy:

# ---------------------------

# R | R | R | |

# ---------------------------

# U | | U | |

# ---------------------------

# U | L | U | L |

policy = {

(2, 0): 'U',

(1, 0): 'U',

(0, 0): 'R',

(0, 1): 'R',

(0, 2): 'R',

(1, 2): 'U',

(2, 1): 'L',

(2, 2): 'U',

(2, 3): 'L',

}

# initialize V(s) and returns

V = {}

returns = {} # dictionary of state -> list of returns we've received

states = grid.all_states()

for s in states:

if s in grid.actions:

returns[s] = []

# 빈값을 넣어는다 initializize

else:

# terminal state or state we can't otherwise get to

V[s] = 0

# repeat until convergence

# 5000 iterative

for t in range(5000):

# generate an episode using pi

states_and_returns = play_game(grid, policy)

seen_states = set()

for s, G in states_and_returns:

# check if we have already seen s

# called "first-visit" MC policy evaluation

if s not in seen_states:

returns[s].append(G)

V[s] = np.mean(returns[s])

seen_states.add(s)

print("values:")

print_values(V, grid)

print("policy:")

print_policy(policy, grid)

2. MC for Control Problem

- Let’s now move on to control problem

- Can we use MC?

- Problem: we only have V(s) for a given policy, we don’t know what actions will lead to better V(s) because we can’t do look-ahead search

- only play episode and get states/returns

- key is to use Q(s,a)

- we can choose argmax[a]{Q,a}

MC for Q(s,a)

- simple modification

- instead of list of tuples(s,G)

- return list of triples(s,a,G)

Problem with Q(s,a)

- with V(s) we only need ISI different estimates

- with Q(s,a) we need IsI x IAI different estimates

- Many more iterations of MC are needed

- should remind us of explore-exploit dilemma

- if we follow a fixed policy, we only do 1 action per state

- we can only fill in ISI / (ISI x IAI) = 1 / IAI values in Q

- Can fix it by using the “exploring-starts” methods

- we choose a random initial state and a random initial action

- thereafter follow policy

- this is consistent with our definition of Q :

Back to Control Problem

- if we think actually, we’ll realize we already know the answer

- Generalized policy iteration:

- Alternate between policy evaluation and policy improvement

- we know how to do evaluation

- policy improvement same as always : π(s) = $argmax_s$Q(s,a)

Problem with MC

- Problem: same as before - we have an iterative algorithm inside an iterative algorithm

- For Q we need lots of samples

3. Solution

- Similar value iteration

- Do not start a fresh MC evaluation on each round

- would take too long to collect samples

- instead, just keep updating the same Q

- Do policy improvement after every episode

- therefore, generate only one episode per iteration

Pseudocode ``` Q = random, pi =random

While True : s, a = randomly select from S and A states_actions_returns = play_game(start=(s,a)) for s,a,G in state_actions_returns: returns(s,a).append(G) Q(s,a) = average(returns(s,a)) for s in states: pi(s) = argmax[a]{Q(s,a)} ```

Another Problem with MC

- What if policy includes an action that bumps into a wall?

- we end up in same state as before

- if we follow this policy, episode will never finish

- Hack:

- if we end up in same state after doing action, give this a reward of -100, and end the episode

MC-ES

- Interesting fact: this converges even though the samples for Q are for different policies

- if Q is suboptimal, then policy will change, causing Q to change

- we can only achieve stability when both value and policy converge to optimal value and optimal policy

- Another interesting fact: this has never been formally proven

4. MC Control without ES

- Disadvantage of previous control method : needs exploring starts

- Could be infeasible(不可能的) for games we are not playing in “god-mode”

- E.g Self-driving car

- remove need for ES(exploring starts)

- Recall: all the techniques we learned for the multi-armed bandit are applicable here

- let’s not be greedy, but epsilon-greedy instead

- code modification:

- Remove exploring starts

- change policy to sometimes be random

- Epsilon-soft

- But we also use epsilon to decide if we want to explore:

- From now on, we’ll just refer to this as epsilon-greedy

추가 설명

- 즉 해보지 않은 행동에 대해서도 가끔 선택할 수 있게 하는 방법

- 방법에는 두가지가 있다

- On-policy : 결정했던 행동들을 가지고 정책을 평가 발전한다

- Off-Policy : 다른 방법에 의해 만들어진 데이터로 정책 평가와 발전한다.

- Monte Carlo ES는 On-Policy

- Monte Carlo without ES 는 Off-Policy

- On-policy Control 방법은 정책이 Soft 하다. Soft의 뜻은 정책의 모든 확률이 0 이상, 즉 초기에 모든 행동을 일정 확률로 할 가능성이 있다가 점점 결정적인 최적의 정책으로 바뀐다(deterministic Optimal Policy).

- Off-Policy Control은 Epsilon Greedy 방법을 이용하여 랜덤하게 행동을 선택할 확률 최소값은 Epsilon / IA(s)I 이며, 나머지 확률 1-epsilon+epsilon/IA(s)I 로 greedy 행동을 취한다. (1-epsilon에 epsilon/IA(s)I 추가한 이유는 랜덤하게 하는 행동중 하나가 이 greedy로 행동 할 것이기 때문이다.)

- epsilon-greedy 정책은 확률이 π(a I s) >= epsilon/IA(s)I로, e-soft policy의 예이다.

- 즉 exporing starts 가정 없이 탐험을 할 수 없기 때문에 무작정 가치를 따라 Greedy하게 행동하도록 할 수 없다.

- epsilon-greedy policy 또한 정책 개선 이론에 따라 확실히 개선된다. π’를 epsilon-greedy policy라고 하였을 때( weighted average가 1 이고, 가장 큰 수보다 작거나 같다. 아래식은 모든 행동에 대한 확률의 합이 1이 되도록 한 식이다.)

- 결국 정책 x의 가치의 합이기 때문에 이는 상태 가치홤수와 같다. 결국 $q_π$(s,π’(s))>=$v_π$(s) 이므로, 정책 개선 이론에 따라 π’>=π(즉 $v+π$(s)>=$v_π$(s))가 된다.

-

epsilon-soft policy 과에 차이점은 epsilon-soft가 들어갔다는 차이밖에 없다. 동일한 행동과 상태들, epsilon에 따라 랜덤한 행동을 하는 것까지 같다. 아래에 variable $v_$^~ $q_$^~ 이 새로운 환경에 최적의 가치 함수들이라고 하자. 그럼 epsilon-soft policy 는 $v_π$ = $v_π$^~라면 π는 최적이라고 할 수 있을 것이다.

- $v_π$ = $v_π$^~ 로 바꾸면

- Policy iteration은 epsilon-soft policy 에도 적용이 된다는 것을 보였을 것이다. epsilon-soft-poilicy 에 greedy policy를 적용하면 매 step마다 개선이 확실 된다는 것을 보이며, exploring starts를 제거했다.

How often will we reach off-policy states?

- Consider a state K steps away from the start

- the probability that we get there by pure exploration is small

- we need to run MC many times to converge for these states

5. MC Summary

- Last Section, DP: we knew all the state transition probability and never played the game

- this section: learn from experience

- main idea: approximate the expected return with sample mean

- First-visit and every-visit

MC VS DP

- MC can be more efficient than DP because we don’t need to loop through all states

- But also means we might not get the “full” value function, since some states will never be reached or reached very rarely

- more data -> more accuracy

- We used exploring starts to ensure we had adequate data for each state

MC Control

- Use Q instead of V

- No look-ahead search

- Problem: MC loop inside another loop

- We took the same approach as value iteration: update the policy after every episode, keep updating the same Q in-place

- Surprising: it converges even though the samples are not all for the same policy

- Never formally proved to converge

- we then removed exploring starts assumption by replacing it with epsilon-greedy

- MDPs are like different multi-armed bandit problem at each state

Reference:

Artificial Intelligence Reinforcement Learning

Comments